More than 100 people die from opioid overdoses each day in the United States. Just this week, the National Safety Council’s analysis of preventable deaths identified opioid overdose as the No. 1 cause of unintentional death; for the first time, Americans are more likely to die from an opioid overdose than a vehicle crash.

What are opioids?

“Opioids are drugs formulated to replicate the pain-reducing properties of opium. They include both legal painkillers like morphine, oxycodone, or hydrocodone prescribed by doctors for acute or chronic pain, as well as illegal drugs like heroin or illicitly made fentanyl.” (CNN)

How we got here

The history of pain management is relatively recent, and until the late 20th century, pain was severely undertreated. Early discoveries of pain management treatments for postoperative cancer in the 1990s led to new applications and strict standards of management for a wide spectrum of acute and chronic pain. As it turns out, opioids are good at getting rid of all kinds of pain — almost too good. This newfound desire to eliminate pain — instead of manage it — led to overprescription and widespread misuse of opioids.

“In the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies reassured the medical community that patients would not become addicted to prescription opioid pain relievers, and healthcare providers began to prescribe them at greater rates. This subsequently led to widespread diversion and misuse of these medications before it became clear that these medications could indeed be highly addictive.” (National Institute on Drug Abuse)

Prosecutors and investigative journalists are still uncovering details of how Purdue Pharma, makers of the prescription painkiller OxyContin, deceptively marketed the drug and concealed knowledge of growing abuse. A number of states have filed lawsuits against Purdue Pharma, as well as other drugmakers and distributors.

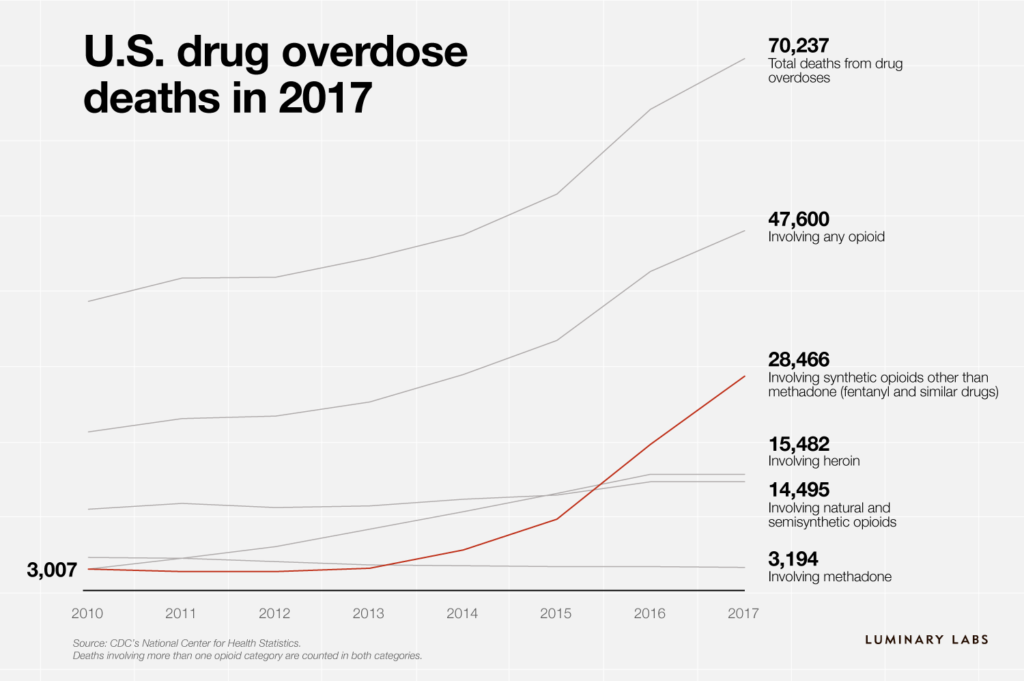

This increasing pressure — along with better awareness of the value of pain and the options for managing it — has led to a declining number of opioid prescriptions and supported attempts to reduce the number of new drug users. But suppliers of illicit drugs — heroin and black-market fentanyl — have rushed in to fill the void for those who already use opioids. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that’s 100 times more powerful than morphine, is driving dramatic increases in overdose deaths.

“Overdose deaths are higher than deaths from H.I.V., car crashes, or gun violence at their peaks. The data also show that the increased deaths correspond strongly with the use of synthetic opioids known as fentanyls. Since 2013, the number of overdose deaths associated with fentanyls and similar drugs has grown to more than 28,000, from 3,000. Deaths involving fentanyls increased more than 45 percent in 2017 alone.” (The New York Times)

Illegal drug dealers are increasingly selling opioids laced with fentanyl. The unpredictable potency makes these drugs even more dangerous, and first responders say it’s increasingly difficult to reverse overdoses. Illicit fentanyl is often purchased online and shipped directly to buyers; China is the largest source, but packages can come from anywhere, and the small parcels are difficult to detect.

What’s at stake

The number of deaths, though staggering, is not the only result of the crisis. More than 4 million people are “nonmedical users” of painkillers and an estimated 2 million people in the United States suffered from substance use disorders related to prescription opioid pain relievers.

Opioid addiction is impacting millions of families — and their extended communities — across the country. Children and teens are increasingly at risk of accidental exposure and overdose. The steep increase in overdose deaths has led to an unprecedented decline in American life expectancy.

In 2015, nearly 1 million people were absent from the workforce due to opioids, and over the past two decades, lost productivity has cost the U.S. economy more than $700 billion.

Potential solutions

If you ask 30 experts, you’ll get 30 different ideas for how to approach the problem. And with a crisis this big, it makes sense to identify multiple angles and pursue many possible solutions.

The federal government’s Initiative to Stop Opioid Abuse is focusing on three areas: reducing demand and overprescription, cutting off the supply of illicit drugs, and supporting addiction treatment and recovery. The SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act, a bipartisan bill signed into law in 2018, approaches the problem in “hundreds of ways,” from tracking and testing international packages for drugs to allowing health care providers to prescribe addiction treatment medication.

One way to think about the problem and its possible solutions is to divide it into two issues: supply and demand.

Supply

Initiatives that decrease access to opioids are tackling prescription and trafficking. Recently, we’ve noticed:

- Reducing prescriptions. Opioid prescriptions peaked in 2011 but overprescription remains a concern. One recent study found that doctors prescribed fewer opioids after finding out a patient had died from an overdose. Another study found that many emergency department physicians underestimate the number of prescriptions they write, but significantly decrease the number of opioids they prescribe when they’re aware of their prescription rate and how it compares with that of their peers.

- Intercepting distribution. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration launched a global operation to crack down on hundreds of websites selling illegal drugs. The STOP Act, a component of the bipartisan legislation passed last year, will require the U.S. Postal Service to collect and share data with U.S. Customs and Border Protection for international packages in an effort to identify and block delivery of illegal drugs.

Demand

Solutions for reducing demand are finding new ways to treat pain, addiction, and overdose. A few collaborations, launches, and stories we’re tracking:

- Preventing overdoses. Many first responders carry naloxone, a medication that can rapidly reverse opioid overdose, and have used it to save lives; in some communities, libraries and other community centers are teaching employees how to administer the life-saving drug. An app developed by the University of Washington can detect changes in breathing that could signal an overdose. Test strips could help drug users figure out if their supplies have been laced with fentanyl, preventing overdoses from unexpectedly potent drugs.

- Treating addiction. A number of open innovation efforts — the FDA Innovation Challenge, the HHS Opioid Code-a-Thon, Ohio Opioid Tech Challenge, and Empire State Opioid Epidemic Innovation Challenge — have identified solutions for addiction treatment and prevention. The reSET-O app, developed by Pear Therapeutics in collaboration with Novartis subsidiary Sandoz, is a prescription-only digital treatment recently approved by the FDA. Rock Health sees potential for technology-based startups to develop digital treatments for addiction, and StartUp Health announced an Addiction Moonshot to end the opioid epidemic at its 2019 festival earlier this month. We expect to see more novel collaborations in this space.

- Managing pain. In addition to improving misuse and addiction treatment, the NIH HEAL Research Initiative is working with partners to share data and support research that enhances our understanding of chronic pain. Mad*Pow’s Center for Health Experience Design (CHXD), Massachusetts Health Quality Partners (MHQP), and Cigna are collaborating to envision a new tool for communicating about pain. And new options — including wearable devices that use neurostimulation — are offering non-opioid alternatives to pain management.

- Measuring impact. Better solutions often start with better data. The Opioid Data Challenge seeks to better measure overdoses and harms in Canadian communities. (The opioid crisis isn’t limited to the United States.) Scientists also have the ability to “transform sewers into public health observatories,” revealing detailed patterns of opioid use in cities.

Are you studying this problem or working on a solution? We’d love to hear your thoughts — send a message to editor@luminary-labs.com.

Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash.