Three ideas for unlocking equitable progress through open science hardware and software.

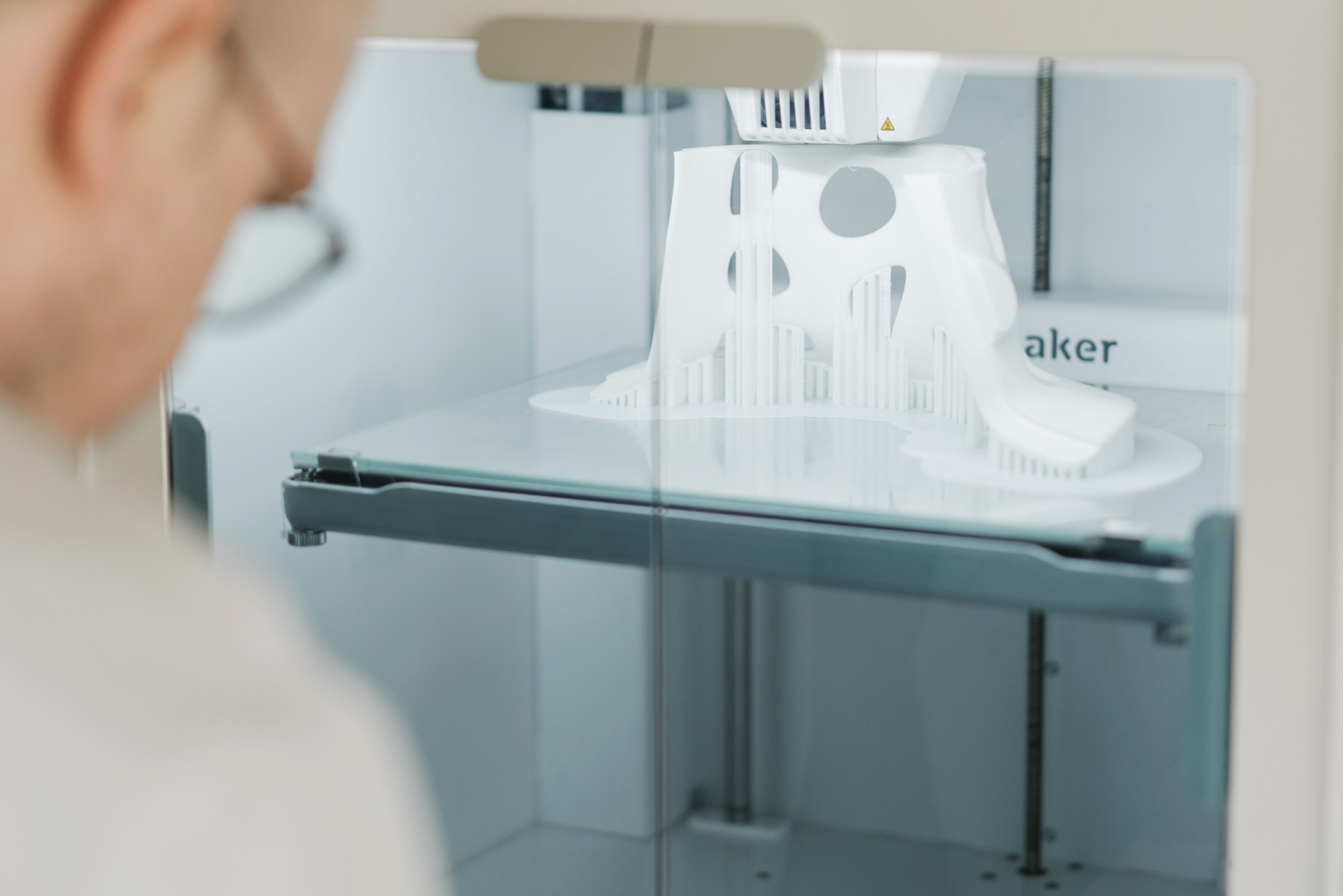

Even before Luminary Labs designed and produced its first open innovation challenge in 2011, we were experimenting with open methodologies. And our interest in new and novel ways of working — and all things “open” — extends to open science and open hardware. In recent years, Tool Foundry, a Luminary Labs initiative, advanced accessible tools for scientific discovery by helping tool makers build a foundation for sustainable growth and advocate for the science-curious. We believe that accessible — low-cost, high-quality, easy-to-use — tools can inspire a deeper interest in science and empower people to indulge their curiosity, explore their environments, and solve problems relevant to their own communities.

Last month, I joined a diverse group of federal, nonprofit, and private-sector experts in Washington, D.C., for an “Open Source for Open Science” roundtable hosted by the Wilson Center Science and Technology Innovation Program and the Open Science Hardware Foundation. The roundtable explored how open source software and hardware can advance open science — and what actors across ecosystems must do to realize that potential. This lively and inspiring discussion highlighted both exciting opportunities and daunting barriers. In particular, these three big ideas deeply resonate with our work at the intersection of science, infrastructure, and open innovation.

“Open” doesn’t mean unmanaged.

To many, “open source” implies total decentralization and self-management; from this vantage point, staying out of the way is what lets thousands of flowers bloom. In reality, creating and caring for open science ecosystems involves a surprising amount of thoughtfulness and structure. Planning, monitoring, and management of open software and hardware ecosystems help ensure that discoveries build on one another, new faces and voices can access and add to conversations, and benefits are distributed equitably. There was much talk of the inherent differences between software, data, and hardware in the “open” context. One attendee noted, “you can’t just make a GitHub for hardware” — some principles may apply, but different applications need different management systems. And in the coming age of open genomes and biofabs, synthetic biology and the bioeconomy may combine aspects of both open hardware and software ecosystems. An emerging solution is the open source program office (OSPO), which oversees an ecosystem’s strategy, lexicon, guardrails, compliance mechanisms, and more. While this model is not new in the private sector, at least one federal agency recently established an OSPO — and greater adoption of such management systems across sectors would accelerate adoption and align incentives.

Open science needs a business case.

Many discussions on this topic understandably focus on technical barriers to expanding open hardware and software. Yet this particular group keenly understood that, while human ingenuity knows no limit, budgets certainly do. One attendee noted that, despite having a philosophical preference for open sourcing, the reality is it costs their organization 5-8% more than simply developing something privately or in-house. This comment suggests that practitioners need to show how the relative economic benefit of open science justifies the investment. In addition to highlighting the need for lower-cost tools, this anecdote reveals how some institutions fundamentally undervalue the upside of democratizing science. Beyond the societal benefit of solving public problems faster, open source tools lower barriers and expand the diversity of experimentation and learning; and research has begun to quantify how open-source software can generate measurable GDP growth. Further research could also quantify just how much rent is extracted by “proprietary” tools that create minimal value relative to what people make with them.

Open science needs a skilled workforce.

A strong business case for open science would challenge critics and encourage investment. But business cases rely on the assumption that there is a critical mass of people who possess the basic skills required to adopt and use the hardware or software tools and ecosystems open to them. Many of today’s jobs already require advanced math and other technical skills. The powerful open hardware and software tools on the horizon will demand even more and different skills (for example, baseline understanding of networks, programming concepts, data, workflows). No-code and low-code open platforms meet users where they are and can help them develop skills, but not all open software — let alone open hardware — can apply such approaches. For truly accessible open science, all sectors need to be making catch-up investments in upskilling adults and teaching more future-focused skills in grades K-12. Many attendees are thinking about or working on this need, and it was inspiring to meet leaders like Dr. Kari Jordan, Executive Director of The Carpentries. This innovative organization exemplifies open science and accessibility principles; its training programs have reached 100,000 learners and counting since 2012.

Democratizing science can help society solve many more of the thorny problems that stymie equitable progress. To get there, the world will need more and better open hardware and software tools — as well as more intentional investment in the systems, business models, and people that take “open source” from a concept to concrete impact.

—

Photo by Tom Claes.